A website dedicated to athletics literature / Biography

Introduction:

F.A.M. Webster is one of the most important names in the history of athletics in the 20th century in Britain. His significance does not lie merely in the fact that he wrote more than thirty books on athletics, the Olympic Games, and related topics, nor in the Amateur Field Events Association, and the Loughborough Summer School, both of which he created, nor because he wrote about, taught, and generally championed the field-events in Britain at a time when others didn’t, but because he is an enduring example of how one person, by the power of his own enthusiasm, energy, commitment and persistence, and in the face of the indifference and even hostility of 'official' bodies, can inform, motivate and inspire others, and so leave behind a legacy that lasts long after his own day.

The F.A.M. Webster Collection comprises a biographical note of F.A.M. Webster's life, written by his grandson Michael Webster, and a list of all his published books; and a separate list of his books on athletics and the Olympic Games. The Collection consists of ten titles written between 1913 and 1948, covering - athletics coaching, men's and women's events, the Field Events, and the Olympic Games.

Frederick Annesley Michael Webster (1886 - 1949)

A biography

By Michael Webster

2016

Frederick Annesley Michael Webster was born on 27th June 1886 in St Albans, the only child of Frederick Richard and Louisa Webster (Wells).

His father was a surgeon, and his mother the daughter of Michael and Mary Wells of Holme Park near Peterborough. His father died in 1897 when F.A.M. Webster was just short of his eleventh birthday. Thus his upbringing was almost entirely in the hands of his widowed mother Louisa. They lived at 18 Chequer Street, St Albans.

1890 Raveley House, Chequer Street, St Albans.

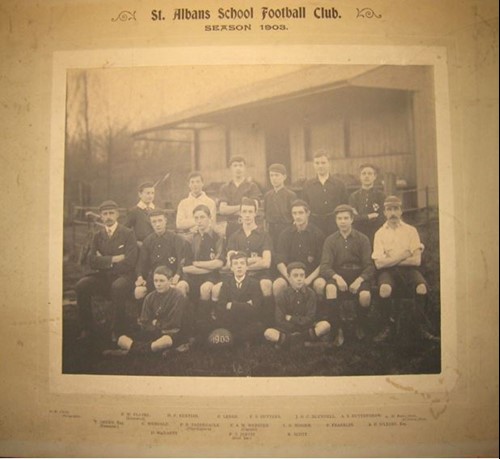

In January 1898 he entered St Albans Grammar School, and although there is no record of his first three years at the school, he played a full part in the school’s activities. These were principally on the sports field, where he excelled in athletics events, but also included first eleven representations in cricket, hockey and soccer.

His enthusiasm, it seems, may often have surpassed his skill -

Cricket - ‘He hits wildly at most things, with more coaching might make a fair bat. Does not keep his place in the field.’

Hockey - ‘He makes a good and somewhat pacy forward, fields the ball well and follows up hard; passes too wildly and is apt to get out of his place.’

Football - ‘A good kick with some command of the ball. Must learn to keep his place and avoid dribbling.’

Nonetheless, in 1903 he was Captain of Football.

1903 St Albans School Football XI

In the same year he was a founding member of the Cadet Corps where he later became the Senior Cadet.

It was however on the athletics field that he was almost supreme. He and his contemporary, L.G. Hosier, whom he described as “the greatest all round sportsman he had ever come across”, fought the closest of battles throughout their time at St Albans. Sports Day 1904 was described thus:

The battle between Webster and Hosier for the Old Boys’ Cup was a stern one. It was practically decided by the Hurdle Race which Webster won by inches. The final score was Webster 21 points, Hosier 20 points. In warmly congratulating Webster on his second win, we express our admiration for Hosier’s plucky efforts to wrest the championship from him.

His athletics grounding and achievements at St Albans surely fired his passion for athletics throughout his life.

His time at St Albans School came to an end in 1904 but F.A.M. Webster continued to be involved with the school. He left in the summer but was back for the Corps dinner in December, having played in the Old Boys soccer match in the afternoon. He missed the athletics in the spring but again attended the Corps dinner where he was recorded as having joined (2nd Beds). The following year he won the Old Boys 100m race in 11.2 secs but speeded up a bit for the regimental sports in Colchester when he recorded 10.8 secs. He also speeded up for the hurdles, 18.6 secs, and high jumped 5ft 4 inches.

It is interesting that Webster was still competing in the Old Boys Race in 1911 when he first won the national javelin championship. He was unable to defend his title in 1912 due to a crocked knee which was always causing him problems after badly injuring it playing soccer for the Old Boys.

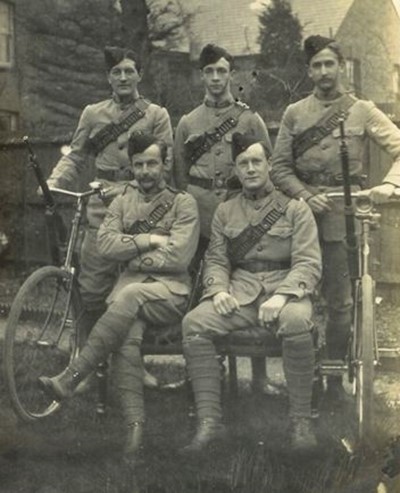

As well as athletics, St Albans School provided his initiation into the military world through the Cadet Corps. While still at school he joined the local Territorial Army force, the 2nd Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Regiment. Here he was part of the Cyclists Section, attending a series of camps with them between 1902 and 1908.

Cyclist Section, 2nd Beds & Herts Regiment TA.

There is not much evidence of what F.A.M. Webster did immediately after leaving St Albans School in 1904; the school register showed that he entered an Accountant’s Office.

Presumably though, he trained as a surveyor, hence the notice of the dissolution of a partnership of ‘Architects & Surveyors’ in 1912 and his description as “Architect, Surveyor & Valuer” in the 1911 Census.

He continued to compete at athletics meetings and, in 1908:

- In the 6th Division Army Sports held at Colchester, F.A.M. Webster won the following races - 1st High Jump 5ft 2in, Long Jump 20ft; 2nd 100yds; 3rd 120yds Hurdles. Twenty feet constitutes a record for the Long Jump at these sports.

- In the Post Office sports at the Stadium, F.A.M. Webster was first in the Strangers’ Open Hurdle Race. In the 100yds at these sports he ran 3rd, beating H. St. A. Murray, who was a New Zealander, but who represented Australasia in the 1908 Olympic Games. (He ran in the 110m Hurdles, but finished second in his heat, and so was eliminated).

- In the sports of the Finchley Harriers at the Stadium, F.A.M. Webster took 3rd place in the 100yds Open.

His involvement in athletics continued - he won the Javelin at the English National Championships in 1911 and again in 1923.

1923 English National Javelin Champion, again.

He competed for and trained the Bedfordshire County Athletics Team for many years, continuing past the age of forty when he competed alongside his sixteen year old son, Dick.

1930. Bedford County Athletics Team

Field Events

In 1910 his advocacy of proper training for Field Events was given an official platform by the formation of the Amateur Field Events Association, of which he was Hon. Secretary with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle as Chairman. The following is a letter to The Times, written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in 1912.

THE OLYMPIC GAMES

SIR A CONAN DOYLE’S SUGGESTIONS TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES

Sir, - All who have our reputation as athletes at heart owe a debt of gratitude to your Correspondent at the Stockholm Games for his very clear and outspoken comments upon the situation. We can now see the causes of past failure. The question is how far they can be removed in the future, and what steps should be taken to that end.

Everyone is agreed as to our possessing the material. There remain only two factors — the money and the management.

To make worthy preparation we must have liberal funds. If the public do not provide them, then they can blame no one but themselves for our failures. I think that where the Olympic Council is most open to criticism is that they have not kept sufficiently in touch with the Press and the public, by explaining what had to be done and what was needed to do it. I am sure that with fuller knowledge the public would have responded more fully. Can we not find among our rich men someone who will make the Games his hobby and be the financial father of the team? How could a man spend his money better? But, failing that, we must all make an effort - and the sooner the better, before we have lost the stimulus which our defeat provides - to secure ample funds for doing everything which money can do to put the flag at the top in Berlin in 1916. I hope that a strong and influential appeal for funds will be made in the immediate future, with some reassuring statement as to how they will be expended. If the public does not respond it will prove that there is no national interest in the Games and that our case is serious. But I am convinced that this is not so, and that the money will be forthcoming.

Having secured a good war-chest, what are the other measures which should be adopted?

1. The first is the formation of a British Empire Team, which you have already discussed, and which seems to have met with general acceptance.

2. Annual, or even bi-annual, games should be held on the Olympic model each year from now to 1916. Every Olympic Stadium event should be contested in these with handsome prizes. They should be held alternately in the provinces and in London. In this way we would thoroughly understand what material was available, and we would accustom our athletes to metre distances, and to the unusual competitions, such as the discus and javelin. I may say here that there is a small society existing, of which I have the honour to be president, called the Field Events Association (Hon. Secretary, F.A.M. Webster, 161A, Strand, W.C.), which endeavours to promote these abnormal events, and which has already obtained very gratifying results.

3. We must bring our full strength into the field. It should be recognised that just as all counties give up their best men for an England match, so Bisley, Wimbledon, or Henley must not detain our Olympic champions. The absence of our tennis players and of our yachts this year was a deplorable thing. There should be such a public spirit over the Games that it would become impossible for anyone to throw obstacles in the way of our complete representation. As a mark of such public interest the team should have a public send-off and a public reception upon its return.

4. The team should be brought together into special training quarters for as long a period as possible before the Games, with the best advice always available to help them. At the Games themselves every effort should be made to keep them under the most healthy and comfortable conditions.

5. In every branch of sport someone must be responsible and on the spot to see that our men are fulfilling every condition. Then such fiascos as the two young officers disqualified in the riding would be avoided.

There is, as I understand, to be an important meeting of those interested in the question during the week, and it is to be earnestly hoped that some way will be found by which the central controlling body (who have, I believe, in some things done excellent work with very insufficient means) will be brought into closer touch with public opinion.

Yours faithfully,

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE.

Windlesham, Crowborough, Sussex, July 29.

In addition to athletic competitions and his work to establish the Field Events Association Webster now embarked on his writing career, eventually publishing 114 titles on athletics, novels, military manuals and history, poems and adventure stories for children. His range was quite remarkable and reflected his experience, wide interests, and enthusiasms.

“The two great English technical writers of the pre-war period were undoubtedly F.A.M. Webster and Guy Butler. The latter was strongly running-based and pioneered the use of sequence photography. Of the two, Webster was the more eclectic and added to his technical knowledge a profound understanding of the history of amateur athletics. It is a revelation to re-visit the works of Webster, to reflect that for over forty years he toiled without complaint and with little recognition in a sport whose establishment resisted coaching and all that it represented. Hundreds of thousands of words poured from his pen, into a sport strongly based in public schools and universities but weak in Britain’s harrier-based clubs. Understandably, many of Webster’s technical and training ideas have failed to stand the test of time but it must never be forgotten that in the first half of the century he undoubtedly led the world of athletics coaching. The sport owes him a great debt.” Extract from ‘An Athletics Compendium’

His first publications included: in 1913, ‘Olympian Field Events: Their History and Practice’ and, in 1914, ‘The Evolution of the Olympic Games’.

“It is only since our dismal failure at Stockholm in 1912 that the modern Olympic Games have aroused any vital interest in the mind of “the man in the street”, and even then it has been a mere passing feeling of shame that we should fall so low as to be beaten be even the lesser European nations, who for generations have been our pupils in all sporting pastimes … My desire, in offering this book to the public, is that a better understanding of the Olympic movement may be acquired and a greater interest in athletics generated in the minds of the rising generation …. While our youths prefer to watch rather than to practise the rough old games which first gave us the brave and devil-may-care spirit which has won us possessions the wide world over, it will be a courageous or a very foolish man who will maintain that the bull-dog breed is sound as of yore, in the days of the prize-ring and wrestling-booth.” Preface to ‘The Evolution of the Olympic Games’, 1914

Military Career.

Even at the relatively young age of twenty eight his experience of Volunteer soldiering was such that on 6th August 1914 he was tasked with raising two battalions of the Wandsworth Volunteer Training Corps, equivalent to the later Home Guard. He also published a number of military handbooks and training pamphlets, notably ‘The Volunteer Training Corps Handbook’ which was reviewed in the Spectator Magazine:

"The Volunteer Training Corps Handbook", by F.A.M. Webster. London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1915.

From a "V.T.C." HANDBOOK by F. A. M. WEBSTER, who has had considerable experience in both the old Volunteers and the Territorial Force, is now doing good service as Regimental Commandant - a rank corresponding to Brigadier-General in the Army - of the Wandsworth Regiment of the Volunteer Training Corps. He estimates the strength of the new organization, which has sprung up throughout the country under the stress of the Great War, on the lines of the Home Guards which were suggested in our columns a year ago, at two million men - who are either over the military age or are unable, for good and sufficient reasons, to enlist at present. Mr. Webster's own regiment is well known to be one of the most efficient units of the V.T.C., and he has now published a concise handbook, based chiefly on his own experience, which seems to us likely to be extremely helpful to both the officers and the members of similar units which are in a less advanced stage of training. Mr. Webster points out that the Volunteer Training Corps may be of the greatest service in the event of raid or invasion, since their local knowledge of the ground should go far to supplement any deficiencies in manoeuvring skill. He especially urges the Commandants of units in the neighbourhood of the coast "to arm and uniform their men with the least possible delay, and to give them such a training in field-work over their own countryside as will not leave a road, lane, or field-path unknown to them; in other words, insist that officers, N.C.O.'s, and men alike make a thorough study of the topography of their own particular locality." Shooting and digging are the matters of primary importance, of course; but in such guerrilla warfare as the Volunteers would have to undertake in the case of invasion the men “must be able to kill, dress, and cook their own meat, to build their own huts or temporary bivouacs, and they must learn to travel with their wardrobe in a haversack, for no transport for food and stores will be available, or, for that matter, advisable.” Mr. Webster sketches an excellent programme of training, and gives some valuable suggestions as to the formation and administration of units which may be studied with advantage by those engaged in getting up Volunteer forces in their own districts. The Spectator 28th August 1915

Having raised the Wandsworth battalions he was then appointed as Adjutant of 2nd/6th Battalion South Staffordshire Regiment on 20th May 1915. He received his Territorial Commission on 15th May 1915.

1915, Adjutant 6th Bn South Staffordshire Regiment

However, on 22nd December that year a Medical Board described him as ‘Unfit for General Service’. What the cause of this was, we don’t know.

One of his greatest friends, Alfred. E. Flaxman, was in the same regiment. Flaxman was an outstanding athlete having represented Britain in no less than four events in the 1908 Olympic Games. He was F.R. (Dick) Webster’s godfather.

F.A.M.Webster & Alfred Flaxman

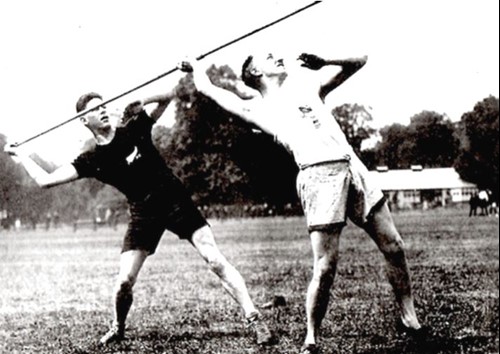

Although Flaxman went to France and was killed on the first day of the Battle of the Somme there is no evidence of F.A.M. Webster serving in France. It is speculation that he was never fit for front line service because of the damage to his knee sustained in 1912 while playing football for St Albans Old Boys. Photographs of him throwing the javelin post-war show his knees heavily bandaged and he was invalided out of the Army in 1919.

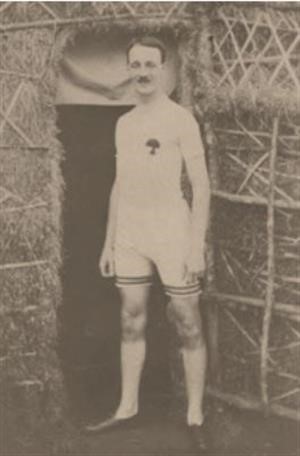

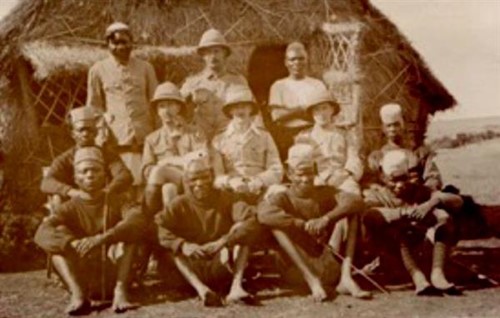

Having, it seems, spent much of the war in a Territorial Training Regiment he eventually persuaded the powers that be to post him to East Africa to join the King’s African Rifles. On 20th February 1918 he left England for East Africa. The campaign in East Africa was past its peak by the time he arrived so there was time for plenty of other activities, including a lengthy safari. It was here that he must have acquired much of the material for his many books set in Africa.

1918 East Africa

King's African Rifles

F.A.M. Webster left East Africa on 13th January 1919. The next six months were mainly taken up with Medical Boards which culminated in him being unfit for military service and relinquishing his commission in July 1919.

On 14th September 1939, aged 53, he applied unsuccessfully to be enrolled in the Emergency Reserve of Officers. However, in July 1940 he rejoined the Army in rank of Captain, serving with the Army Physical Training Corps, and in November 1943 was promoted to Lt Colonel. He was appointed to the staff at Eastern Command where, it is assumed, he supervised the physical training of the troops in that area.

1944 Eastern Command

Marriage and Family

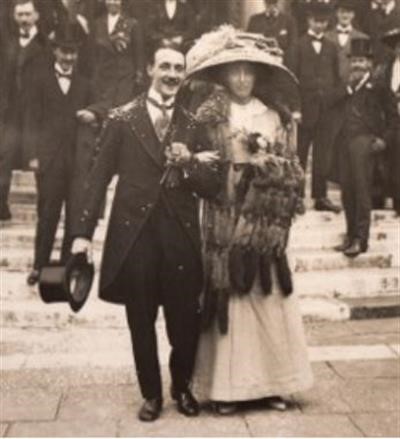

We must retrace our steps to the years before 1914 when he met and married Allison Mary Roberts, a doctor’s daughter in St Albans.

1911 Wedding

After their marriage on 12th October 1911 at St Mary’s le Strand they built a house in Harpenden, Hertfordshire. It was here during the war years that the family grew to include ‘Dick’, born in 1914, Joan in 1916, and Peggy, in 1918.

Peggy, Joan and Dick hurdling

As they grew up, the three children were encouraged to try their hand at every athletic event, supplied with the correct juvenile equipment by their father. Every Sunday a number of boys used to come out from school to practise and be coached. There were holidays at Bacton on the Norfolk coast where families joined together for coaching and athletic sports. F.A.M.Webster’s son, Dick, had been introduced to the pole vault from an early age and was taken to the Olympic Games in Amsterdam in 1928 and to Darmstadt for the World Student Games in 1930. The many years of coaching were rewarded when Dick represented Great Britain in the Pole Vault at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, finishing in 6th place.

1936 Berlin Olympic Games. F.R. Webster, 6th - Pole Vault

Athletics Coaching

F. A. M. Webster’s outstanding contribution was the recognition that improved performances would only come through the proper study and practice of athletic techniques. This he achieved through both his writing and his coaching, particularly with the establishment of the Summer School at Loughborough.

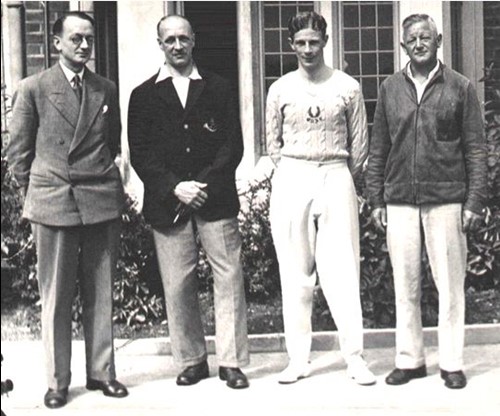

1935 Summer School Loughborough

(J.W. Bridgeman, F.A.M. Webster, Jack Lovelock & Jaakko Mikkola)

“The leading British thinker on coaching in the inter-war years was F.A.M. Webster. He was educated at public school and was a former officer in the army. Webster was a prolific writer on the subject and published around 20 books on coaching from 1913 up to 1948. He had also been coach of Bedford School, which won the Public Schools Challenge Cup eight times in a row. Webster himself had won the AAA's javelin competition in 1911 and 1923. Interestingly, he had been coached by Mussabini in 1923 when Webster was then 37. Symbolically at least, it represented a bridge between two different generations of coaching traditions: the empirical and the scientific. However, whereas Mussabini coached Olympic champions, Webster coached none.

Despite these credentials, Webster was a bit of an outsider and, although he aspired to amateur values, he was not a member of the Achilles Club nor, initially, did he have a role with the AAA. Moreover, he was not afraid to upset the sporting authorities. In 1936, for example, he criticized the International Athletic Board of Great Britain for its preference for track races over field events and the lack of investment in coaching. In 1922, he had written a letter to the AAA and made reference to his books on throwing, jumping and steeplechasing; and it decided to purchase fifty copies of each to distribute around the country. In the lead-up to the 1924 Olympics, the AAA had offered him the post as honorary coach for field events at the White City and Crystal Palace. He turned this down, though, and instead offered to act as coach for the whole country as well as volunteering a list of lectures on field events he had arranged to give. However, the AAA rejected his proposals and appointed Sergeant Starkey as its field events coach.

Nevertheless, this initiative gives an insight into his ideas and his own ambitions for improving coaching standards in British sport generally, which he described as ‘appallingly inadequate’ especially in track and field athletics. It was a situation he was keen to contrast with other countries:

"In foreign countries the necessity for adequate instruction is accepted as a matter of course and the professional coach takes his proper place in the communal scheme of things … In Great Britain we have maintained a strangely illogical outlook - that there is something unfair about winning through the help of a professional coach".

Webster's approach and attitude reflected the burgeoning professional and scientific middle classes that increased rapidly from the 1930s. Social status, though, was still important and in business a managerial style developed that valued social confidence over expertise. Nevertheless, in athletics Webster seemed keen to bridge the two. What made Webster stand out from his contemporaries, who were mainly products of the harrier tradition, was that he devoted much of his attention to field events. Field events were the poor relations of British athletics. Even Mussabini admitted in The Complete Athletic Trainer that he had little expertise in this area. Webster brought a more scientific and rational approach to field events, which at the Olympics had been dominated by the Europeans and Americans. While Douglas Lowe, winner of the 800m at both the 1924 and 1928 Olympics, for example, briefly explains the basics of field events in his 1935 Track and Field Athletics, Webster devotes a chapter to each event through the use of complex training tables. He was also willing to adopt contemporary scientific ideas such as A.V. Hill’s work on oxygen debt, biomechanics and diet. In addition, Webster drew on the work of Pavlov to theorize about the effects of anxiety on the efficiency of an athlete's circulation and digestion.

In 1934, Webster was appointed the first director of the AAA summer school at Loughborough. In the first two years, coaches from Finland had attended: Armas Valste, Finland's chief Olympic coach in 1936, and Jaakko Mikkola, later head coach at Harvard University. The course lasted three weeks, with the first two weeks open to professional coaches and ‘schoolmasters, sports officers, welfare supervisors and others who wish to become efficient coaches in athletics’. The final week was given over to the coaching of field event athletes only. Two years later, in 1936, Webster founded the School of Athletics, Games and Physical Education at Loughborough College.

Webster was also a patriot and he used his position as the editor of a brief running publication The Athlete (1936-1937) to pontificate on a number of topics, especially Britain's sporting performances, which he felt were of national importance. Like others before him, Webster argued that “performance in international competition has become a matter of national prestige” and that British teams needed better preparation as well as better coaching. He exclaimed that “To-day, there is an ever growing demand from schools, Service units and athletic clubs for the services of athletic coaches but where are such coaches to be found in Great Britain? The field is ready for tilling but the husbandmen cannot be found”.

From: Knox to Dyson: Coaching, Amateurism and British Athletics, 1912-1947, by Neil Carter, 2010

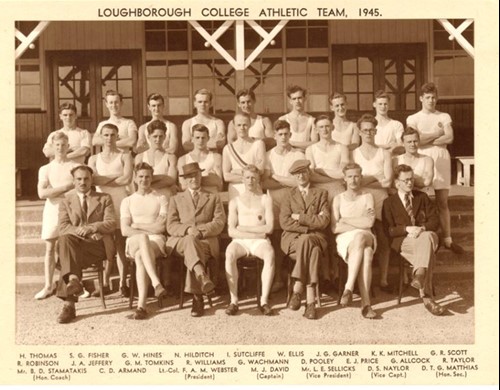

As well as establishing the Summer School he designed a new athletics stadium which was built using student labour. Their reward was a cup of tea and a bun! He remained President of the Loughborough Athletics Club until after World War II.

1945 Loughborough College Athletics Team

Fast Arm at Stamford Bridge

“It was 1928, thirty years before professors of aerodynamics began designing special steel javelins to woo the breeze. Stanley Lay stood at the Stamford Bridge ground holding a spear of ashwood.

These were the British championships and he wanted the javelin title. Ahead lay the Amsterdam Olympics; behind him, 12,000 miles away in New Zealand, a thousand hopes for the javelin thrower from Hawera, the young man of 22 with the very fast arm. In New Zealand he was his own coach; others, less qualified, could report on his throws; none could diagnose.

But in England, in London, there was such a man, Captain F.A.M. Webster, famed throughout his land and abroad as an authority on every branch of athletics. Distance runners and pole vaulters alike listened to him with respect.

Lay listened, too, on the first grey Monday morning on Battersea Park. Lay had a very good build, said Webster. Lay said it was from deep breathing exercises every day. Well, he had a good build, said Webster, and he certainly had a fast arm. And temperament? Perfect. Lay rarely fouled a throw. The technique, then. Webster had seen him throw on Saturday. The run up was nice and smooth, but the arm action was at fault. He called now for a maximum throw from Lay, so Lay threw very hard. Webster was interested. He wanted to know, had Lay ever broken a javelin? Yes, as a matter of fact he was the only person in New Zealand who had ever broken a javelin in mid-flight. The thing had started quivering as it took off, and then suddenly snapped. It had happened several times. Just so, said Webster. It was because Lay pulled too hard in the middle of the javelin, bowing it as he threw. It left the hand shaking and spinning. A javelin was supposed to be pushed, like a dart, not thrown like a meat pie. The answer was to “palm it up” - with the final, vital flick of the wrist, push up as well as out. The hand was not to pull but to lift.

Already Lay was fascinated. He started with some experimental throws, some from the stationary position, some with a walking approach, all with deep concentration. When his arm began to tire he quickly stopped. He had by this time made twenty throws and Captain Webster had taken twenty photographs. They would come back at ten in the morning, said Webster. They went their ways into the grey afternoon, Lay to his dinner and early bed, Webster to develop his films.

The unseasonal fog persisted overnight, but Lay and Webster emerged from it to meet at ten o’clock on Battersea Park. Webster had two piles of photographs and sheets of typewritten paper. “you can keep these,” he told Lay. Lay took the photos and notes, amazed. The man was a complete athletics enthusiast, seeking technical perfection and a fulfilled potential, regardless of nationality. If a New Zealander were the most exciting prospect in a decade, then the New Zealander was to have all the help he needed to beat the Englishmen for the British title.

Lay looked at the photographs, each one numbered, and the notes, also numbered. Lay’s “number 4” was compared with a throw by Myra, the great Finn who once held the world record. In others he was matched with Lindstrom, the Swede who held the current record of 218 feet 6 7/8 inches.

“Your weight is moving to the left here …” “Your arm has moved away from your head …” “You are going to slice this throw …” “This finish is good …” “See the bend in the shaft … not palming it up …”

Lay pored over the photographs. He started throwing, with the javelin and without it, with running throws, walking throws, and little flicks of the wrist. Palm it up, Webster kept saying, push it up and out. Gradually Lay’s javelin stopped taking off almost vertically into the sky, shaking and spinning. It lifted with the throw and left almost horizontally, as smooth and straight as a torpedo from a tube.

. . .

The crowd watched for the last throw…… As Lay walked easily back to his mark he could be seen to place his hand over his heart. His heart? No, what he felt for was the little smooth object sewn at the back of his silver fern, a greenstone tiki presented by the Maori people of Hawera. It was there.

He turned and looked down the field, to the judges by the throwing line and the judges standing quite still in the distance with the little marker pegs and flags sprinkled around them. It was very hot but he could not feel the heat now. He brought his feet together, his javelin up, leant forward and let himself slip easily from the mark. Nicely under way now, springing with short, elastic strides. His body loosely erect, left arm swinging free at his side. His right hand brushing his ear, holding the javelin close to his head, lightly, as if in suspension. Faster now, bounding towards the check point just twelve feet from the throwing line. Hitting the check mark fair and square, the springing hop from right foot to right foot, into position, perfectly. Instantly the shoulders twisting sharply from left to right and the carrying arm extended out straight behind him. The body side on and ready, the head staying straight and erect, looking at the sky where the javelin would fly. The straight arm, the fast arm, starting to uncoil. The shoulders straightening with an explosive jerk. The elbow leading the javelin up. Up and out. The final flick of the wrist and it was gone … Bouncing now off his braced left leg, high into the air and landing again, almost overbalancing over the throwing line. Looking up and seeing the javelin heading like an arrow into the blue sky, no trace of tremor along its golden shaft. Not faltering but leaping further away, and floating. Still floating. The officials started to turn and scamper back as it dipped, noise starting to swell from the embankment. The javelin falling now, but passing over the Union Jack, then over the marker for Lay’s second throw, then dipping down for the dark blue flag. A loud shout from each of the three hundred people as the javelin head struck, stuck and stood quivering four feet past the dark blue flag.

Lay stooped balancing on his left leg and stood back waiting for the announcement. It was shouted up to him - 222 feet 9 inches. Then he returned to change. The officials hurried away to check the measurement and make application for a world record.

The thousands of spectators who arrived within the hour had missed the greatest performance of the day at Stamford Bridge. There was no victory ceremony. But 12,000 miles away the town of Hawera buzzed with just as much excitement as when Kingsford Smith flew the Tasman the same year.

The record did not reach the books, however. The Finn, Eino Penttilä, had thrown 229 feet 3 1/8 inches [69.88m] the previous October. The British All-Comers Record, however, had been truly broken - by a whole ten feet. When athletics moved from Stamford Bridge years later, Lay’s record still stood. Not until 1957 at the White City ground was his throw bettered at the British championships. By then it was the era of aerodynamics.”

Lap of Honour: The Great Moments of New Zealand Athletics, by Norman Harris, 1963

F.A.M. Webster and the Amateur Athletics Association (AAA)

It was F.A.M. Webster’s espousal of professional coaching that led to his unhappy relationship with the AAA. This had its roots in the difference between Pedestrianism, foot races which were run for money, and bets - a professional sport with professional coaches - the sport of the lower classes, and ‘Amateur’ sport, pursued by universities and public schools, where any suggestion of professional coaching was beyond the pale. The AAA was comprised of those from the ‘amateur’ ethic and initially viewed F.A.M. Webster’s work as ‘professional’. It was not until the Loughborough Summer School was initiated in 1935 under the aegis of the AAA and directed by F.A.M.Webster, that the two parties really came together.

F.A.M.Webster’s son, F.R. Webster, was well aware of this unhappy relationship which was best illustrated when his father was denied entry to the British training base at Uxbridge where he, F.R. Webster, was preparing for the 1948 Olympics. When interviewed in 1966, F.R. Webster described the AAA as ‘those bastards’!

Athletics Writing

F.A.M. Webster’s output of athletics books was remarkable and, importantly, they were the first to articulate the science of athletics.

Between 1913 and 1948 he produced some twenty five books ranging from ‘The Science of Athletics’ to ‘Keeping Fit at Forty’.

It is sad that the recognition of his achievements was delayed until well after his death in 1949.

“If anyone could be described as the father of British athletics coaching it would be Frederick Annesley Michael Webster, best known as Captain F.A.M. Webster.” (England Athletics Hall of Fame Citation, 2012)

“He died in 1949 having transformed the science of athletics.” (Loughborough University Sport Hall of Fame, 2013)

Novelist and Writer

In addition to writing about and coaching athletics, his main source of income was from writing in many other fields - spy thrillers under the name of ‘Michael Annesley’, many stories set in Africa, detective stories, schoolboy adventures, and military history. He has a total of more than a hundred titles held by the British Library. He was also a regular contributor to science-fiction magazines, edited ‘The Athlete’ and produced two short collections of poems. As a journalist, he was a Special Correspondent at six Olympic Games.

During and after World War II he continued to write both novels and athletics books - some 25 books were published between 1940 and his death in 1949.

The following is a list of FAM Webster’s books on athletics, fitness, and related topics -

1913 Olympian Field Events - their history and practice

1914 The Evolution of the Olympic Games

1919 Success in Athletics, and how to obtain it

1922 Athletics Records to date

1922 Hurdling and Steeplechasing

1922 Jumping

1922 Throwing

1925 Athletics

1928 Athletes in action

1928 Athletics for Schoolboys

1928 How to become an athlete, practical hints for boys and girls

1928 Teaching and training athletes

1929 Athletic sports - Track events

1929 Athletics for men

1929 Athletics of today: history development and training

1930 Athletics of today for women: history development and training

1931 Keeping Fit: Home physical exercises

1931 Keeping fit at forty (with J.A. Heys)

1931 Athletes in action

1932 Exercises for athletes (with J.A. Heys)

1932 Official report of the Xth Olympiad

1933 Athletic training for men and boys (with J.A. Heys)

1934 Girl athletes in action

1934 The Games Master’s Handbook

1936 The Science of Athletics

1936-37 The Athlete Magazine

1937 Why? The Science of Athletics

1938 Coaching and Care of Athletes

1938 Indoor athletics and winter training

1938 Lessons in Athletics

1940 Sports Grounds and Buildings

1946 Athletics for women

1947 Great Moments in Athletics

1948 Athletics teaching and training

1948 Olympic Cavalcade

1948 The Glory of the Games

FAM Webster Titles British Library

Michael Annesley Titles British Library

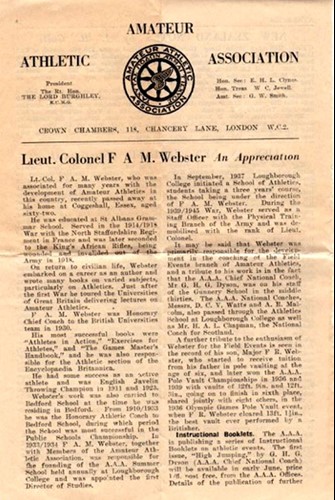

After F.A.M. Webster’s death in 1949, the AAA printed the following appreciation -

Michael Webster

February 2016