A website dedicated to athletics literature / from 1800 to 1860

“Pas de documentation, pas d’histoire”. No documentation, no history. The paucity of literature on Anglo- Saxon athletics in the 19th century does not mean that the sport did not have a rich existence, only that there was little contemporary record of it. It was Marx who said that history was the propaganda of the victors, and Mencken that it was the last person with his finger on the typewriter. This meant that little was recorded at the time of the sport’s cultures from which amateur athletics derived, because most contemporary accounts were penned by the upper classes who had created amateur governing bodies.

The period from 1800 to1860 followed what might well be called a “prehistoric” era. This was one in which athletics undoubtedly existed, but of which little reliable record remains. So, though a myriad of rural games had indeed existed for centuries, they left behind virtually no record of athletics performances. Similarly, match-based foot-racing and time/distance challenges had also existed for centuries. It is, however, difficult to believe that any performances of note were achieved by lightly-trained athletes without spiked running-shoes, on bumpy turnpike roads . The performances achieved in the first half of the 19th century on early cinder tracks would tend to confirm this; no man had run a mile in much less than four and a half minutes before the middle of the century.

The first sprint-based cinder tracks were almost certainly created adjacent to public houses, and were straight, the first curved cinder track being constructed at Lord’s Cricket Ground in 1837. This appears to have been 660 yards in circumference, and a mere five feet wide, and probably had a gravel surface. In 1843, a professional 600 yard hurdles race was held, over 3 ft.6 in. barriers. A caveat here is the possibility that the Sheffield pony track was converted to a running track at some point in the 1835-1845 period, but it is not known exactly when.

The first public appearance of spiked running- shoes was possibly in 1846, when the English runner William Jackson (“The American Deer”) took a pair with him to the USA. By this time, Colpitts of Bishops Auckland was able to boast of shoes “much admired for neatness and affordability”. This does not place an exact date on the creation of spiked running- shoes, only the first mention of their manufacture. It is therefore highly likely that they had gradually mutated from cricket shoes, and had been used in one form or another prior to 1846.

Surprisingly, the word “stopwatch” was first used as early as 1790, when it recorded to half a second. By 1844, this had dropped to a quarter of a second, and by 1865 to one fifth. Strangely, a crude form of electrical timing arrived at the Oxford v Cambridge match at Lillie Bridge in 1874, although we have no detail on how it operated. One eighth stop-watches recorded Donaldson’s 9 3/8th second 100 yard run in 1912, and one tenth watches obtained by 1924. All of the above developments conditioned the accurate timing of sprint-races.

There are two direct sources of the programme of modern athletics, if we define it as a sport containing running jumping and throwing. The first is rural sports, which, as I have earlier explained, existed long before we had accurate records of performance; events such as Dover’s Cotswold Olympics of the 17th century. And it is unlikely that the Cotswold Games appeared as a sudden product of Dover’s imagination; it is more likely that they were simply a sophisticated version of similar gatherings which took place each summer throughout rural England.

The most comprehensive expression of athletics in the 19th century was the Scottish Highland and Border Games. With travel limited to speeds of around 9 mph, most Games athletes only competed in a handful of local Games. This gradually changed with the growth of the national railway system. Some of the Games’ athletes migrated to the East Coast of the USA in the second half of the century and their Games formed the basis of the American collegiate programme. It was therefore a Scot, John Graham, who brought the American team to the 1896 Olympics, and Princeton’s first gymnasium was directed by a fellow- Scot, William Goldie, who is often called the “father” of American track and field athletics.

Similarly, most running consisted of local “challenge” races, and centred round public houses; and the publication ”Bells Life” acted as a national conduit for such challenges. “A Novice of Wendlesfield Heath, who has never won a shilling, will run Edward Evans a 100 yards for £5 or £10 a side. Money ready tomorrow night at Mr. Billingham’s, The Barley Mow, Wednesfield Heath.“ By the middle of the century, dozens of these local challenges ran side by side on the same pages as national challenges. “Deerfoot and Mills. This challenge takes place at Mr. Baum’s, Hackney Wick…….. his appearance has been heralded with much “sound and fury” and tomorrow will show whether it will “signify nothing”, or prove him to be “the flyer” he is said to be”. And by then, there had been created the Pedestrian Carnival, an event usually held in major cities, sometimes featuring races for both professionals and amateurs, but more often confined to professionals.

The direct stimulus to the development of the “running” element of English amateur athletics was the Carnival, which experienced a brief surge in public interest in the early 1860s with the feats at London running-grounds of “Crowcatcher “ Lang and the American Indian Deerfoot . At this point, separate events for the gentry were sometimes held within these Pedestrian Carnivals or in closed “amateur” meetings at tracks owned by professional promoters, often publicans. But this was only the running- element of the athletics programme, and it should come as no surprise that these early facilities were invariably called “running grounds”.

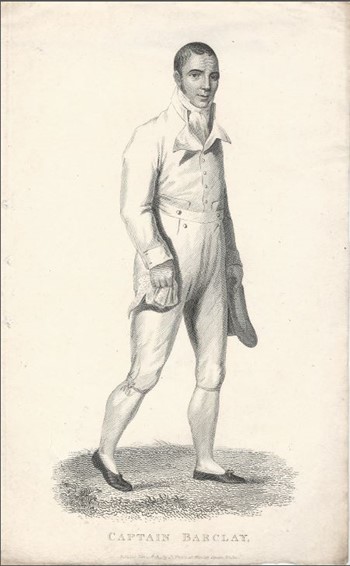

The first great public figure in modern athletics history had been the Scot, Captain Barclay Allardyce, who in 1809 walked a thousand miles in a thousand hours for a wager of £10,000. Barclay, a notable agriculturist, has been claimed as the father of modern athletics training, his most memorable feat being his preparation of the English pugilist Tom Cribb to defeat the black American Molyneux. But Barclay drew upon much earlier training-methods, directly in line with the medical theory of the period, drawn fom Hippocrates, whose mentor had been a coach, Herodicus of Megara.

So much for the early unstructured sources of modern athletics. The roots of the modern amateur movement lay in Britain’s public schools where, in the mid-19th century, sport became an agency by which an unruly student population might be controlled. This meant, in the main, team-activities, for public school sport meant the sublimation of individual desires. The Duke of Wellington famously said that Waterloo had been won on the playing fields of Eton, though Eton’s fields had no existence until after the Napoleonic Wars. But the development of amateur sport, the provision of shape, structure and a code of ethics to athletics did indeed rest with the product of our public schools. Their students moved on to Oxbridge, and instituted inter-college sports. And when as graduates they moved on to do business in London, they created similar clubs and competitions, initially through the Amateur Athletics Club, run by the remarkable John Chambers.

And things would soon change in the world of the professional athlete. The growth of the railway system would see the best Scottish athletes move away from their local games and compete throughout Scotland. This caused some Games to “prize out” the travellers, denying them entry, but market forces soon caused them to re-consider, and introduce separate local events. And “Bell’s Life” of 1860 teemed with local match-races; but in a few years they had almost completely disappeared.

Tom McNab/2014

CONTINUE TO 1860 to 1920