A website dedicated to athletics literature / The Olympic Games and the Duke of Westminster's Appeal

The Olympic Games and the Duke of Westminster's Appeal

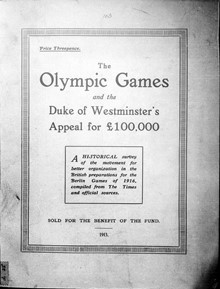

The Olympic Games and the Duke of Westminster's Appeal for £100,000: A historical survey of the movement for better organisation in the British preparations for the Berlin Games of 1916, published 1913.

The author:

This document – ‘the Duke of Westminster Report’ – is arguably the most important publication on British sport in the pre-1914 era. However, it is not known who wrote the document. The potential author probably came from the Special Committee, which was set up to administer the appeal. The Committee was made up of members from the British social and sporting elite:

Chairman: J.E.K. Studd

A.E.D. Anderson

B.J.T. Bosanquet

Theodore Andrea Cook

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

P.L. Fisher

H.W. Forster M.P.

J.C. Hurd

G.S Robertson

Sir Claude MacDonald, GCMG

Treasurer: E. Mackay-Edgar

Secretary: Lieutenant Stuart D. Blair, RN

Arthur Conan Doyle, prolific author and of course creator of Sherlock Holmes, had initiated the debate through his letters to The Times. Doyle was a patriot and a sporting enthusiast who was at the centre of fund-raising activities. Theodore Andrea Cook was a long serving member of the British Olympic Association and was also on the International Olympic Committee. Cook had also been keen to promote the Olympic movement amongst the British public and was a prolific writer. A journalist, he was editor of the Field newspaper and also worked for the Daily Telegraph. As early as 1906, he had warned of British athletic decline and wrote the report for the 1908 Olympics. The committee’s chairman was J.E. Kynaston Studd, later a Lord Mayor of London. He was a notable sportsman but also a Christian evangelist who helped to organise Moody and Sankey’s mission to Britain in 1882. Fellow evangelists included Arthur Kinnaird, the President of the Football Association, and Quintin Hogg, a self-proclaimed muscular Christian, who established the Regent Street Polytechnic. Studd, like the other two an Old Etonian, joined the Polytechnic and was later its President from 1903 to 1931. Another Old Etonian and sporting all-rounder was Bernard J.T. Bosanquet. He played cricket for England and as a leg-spin bowler was famous for inventing the ‘googly’ or ‘Bose’. He was also father of British television newsreader Reginald Bosanquet.

The place of the Duke of Westminster Report in the history of Athletics literature:

The Duke of Westminster Report acts as a history of British involvement with the Olympics as well as a report on the contemporary standing of British coaching. As the sub-title indicates its main purpose was concerned with the preparation of British athletes for the 1916 Berlin Olympic Games.

Published in 1913, the document was a statement on the contemporary attitudes and values that had shaped British sport up until this point; namely the amateur ethos. The rhetoric of amateurism had dominated sporting organisations within the British Isles since the 1870s. Not only was payment for play anathema to amateurs but there was also a dislike of specialisation and coaching, which was deemed to be the domain of professionals and hence associated with the working classes. Amateurism, however, was not monolithic. Instead, each sport had its own approach. Some, like cricket, cycling and football, accommodated professionalism whereas athletics, rugby union and rowing amongst others were much more fundamental in their attempts to exclude working-class professionals; yet coaching was still evident in these sports.

Both because Britain was the pioneer of modern sport and that there was an absence of international competition, improving performance was not a priority for sporting bodies. As a consequence, there was neither critical consideration of the running of sport or the need to improve athletic performance through better coaching. There was also an absence of a coaching culture within professional sports. In football, for example, more emphasis was placed on physical fitness rather than technical skills while the number of trainers/coaches in athletics had declined following the campaign of the Amateur Athletic Association to marginalise professionals. One exception to this general rule was cricket, where coaches had been firmly established at public schools from the mid-1800s, but, in general, as ‘the Duke of Westminster’ embodies in its publication, there had been no previous substantive reflection on the state of British sport at the elite level and on how to improve performance.

This document, therefore, marks a subtle but distinctive shift of attitudes in British sport as well as revealing anxieties within the British sporting establishment over a fall in standards. In particular, whereas the merits of coaching had previously been ignored, here they are flagrantly promoted. International competition and the declining reputation of British sport had provided a stimulus for these changing attitudes and were exposed following the perceived under-performance of British track and field athletes at the 1912 Olympic Games. Despite the success of the men’s 4x100m relay and Arnold Strode-Jackson’s 1500m victory, British athletes were generally eclipsed by their Swedish hosts and the Americans. Later, much attention was drawn to the emphasis these nations had placed on coaching and the systematic preparation their athletes had undertaken leading up to the Games. In contrast, the preparations of British athletes were felt to be not rigorous enough.

This was the context that underpinned the ‘Duke of Westminster Report’ document.

The text:

The document is divided into eight sections with appendices. Beginning with a history of the Olympics, it then conducts a review of the London and Stockholm Olympiads, highlighting American pre-eminence ‘in the Stadium’. In addition, much attention is given to British inadequacies in organisation as well as identifying problems in track and field dating even from the 1906 and 1908 Games (p. 5).

Section 4 sets out the nub of the document – the need for reform: ‘As time passed and there was no sign of any serious awakening to the danger that awaited us at Stockholm … the need of some drastic reform becomes more and more imperative’ (p. 8). It was the unwieldy British Olympic Council which was identified as the main target that required restructuring in order to facilitate better pre-Olympics preparation.

Section 5 (pp. 8-11) charts the origins of the criticism of British performance, mainly through articles and letters in The Times. In particular, it was a letter by Arthur Conan Doyle, who advocated greater preparation, which acted as a catalyst and this view was supported in a Times editorial. The ensuing debate (pp. 11-14) over the intention of reform and its merits or otherwise elicits references to ideas of national and racial characteristics in attempting to make sense of British failure and its Olympic future.

In March 1913 a Special Committee was formed (pp. 14-16). It was charged with the task of appealing for money from the public (the suggested figure of £100,000 was both arbitrary and unrealistic) to fund proposed coaching schemes for various sports. It was a typically British voluntary venture. While European countries were in receipt of state grants and the Americans were buttressed by their collegiate system, the British government declined to provide any funding for British Olympic athletes. Public subscription continued to be the principal British method of raising funds until the introduction of the national lottery in 1994.

Section 8 (pp. 16-30) describes the appeal and the criticisms it brings. In particular, these are centred on a fear of amateur sport being contaminated by ‘the bogey of professionalism’. However, it is countered that if its athletes are not given adequate preparation there is little point in Britain continuing to participate in the Olympics due to the national embarrassment it will cause (p. 17). (One outcome of these anxieties was a sustained debate – discussed in detail in Appendix C – over the possibility of fielding a British Empire team in order to improve performance). Moreover, the claims of creeping professionalism are rebuffed. It is argued that the training British rowers underwent in preparation for their success in 1912 made them no less amateurs and so the same would apply to track and field athletes (p. 18).

Appendix A of the document provides further evidence of the increasing intensity that was devoted to the benefits of coaching. The Special Committee issued outlines of schemes – in co-operation with the Governing bodies – in order to improve the calibre of those athletes selected for Olympic competition. Eight sports are listed. Within its 12-point scheme the English Amateur Athletic Association, for example, planned to promote the sport in the public schools – interestingly, there is no mention of state educational establishments. A series of trials was drawn up in order to filter out the best athletes, while it was stated that ‘the question of training has been considered at length’ (p. 31) and that at specified centres it was planned to appoint an official trainer to advise ‘approved athletes’. Highlighting the traditional British weakness in field events, it was intended to provide proper equipment for these events at various centres. Although not mentioned in this document, for the first time a national athletics coach, William Knox, was appointed in 1914, although he left his position the same year.

Of course, the 1916 Berlin Olympic games never took place. Moreover, there is little reference to coaching schemes again – certainly in the AAA archives – after 1918, and no sense of coaching schemes being revived on this scale again. Nevertheless, this particular document indicates shifting attitudes within British sport in the face of international competition and a re-aligning of amateur values due to the growing recognition of the importance of preparation and coaching to sporting success.

Suggested further reading:

Neil Carter, ‘From Knox to Dyson: Amateurism and British Athletics, 1912-1947’, Sport in History vol. 30 (1) March 2010, pp. 55-81

Dave Day, Professionals, Amateurs and Performance: Sports Coaching in England, 1789-1914 (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2012), pp. 259-65

Tom McNab, Peter Lovesey and Andrew Huxtable, An Athletics Compendium: An Annotated Guide to the UK Literature of Track and Field (Boston Spa: British Library, 2001), pp. xvi, xxviii-xxix

Matthew P. Llewellyn, ‘Advocate or Antagonist’ Sir Theodore Andrea Cook and the British Olympic Movement’, Sport in History, vol. 32 (2) June 2012, pp. 183-203

Arnd Krüger, ‘“Buying Victories is Positively Degrading”: European Origins of Government Pursuit of National Prestige through Sport’, International Journal of the History of Sport, vol. 12 (2) August 1995, pp. 183-200

Neil Carter / 2015

Bibliographic details:

Title:

The Olympic Games and the Duke of Westminster's Appeal

Publisher:

J. P. Bland

Place of Publication:

London

Date of Publication:

1913

BL Catalogue:

General Reference Collection (Microfilm) Mic.A.11037(16)41.d.15-18

"An Athletics Compendium" Reference:

C6, p.70