A website dedicated to athletics literature / Scientific Athletics

Scientific Athletics

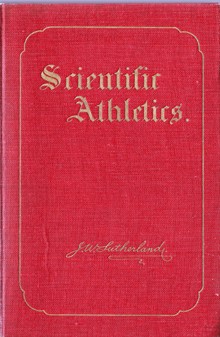

John William Sutherland. Scientific Athletics. 1912

The author:

The family name of Sutherland is very common in the county of Sutherland in the Northern Highlands of Scotland. John William Sutherland was born at Craigton, in one of the highest and most remote parts of Morness in Rogart parish, in 1890. His father, Robert, and his mother, Catherine (née Mackay), already had an established family and John William (who was known in the family as Jack) had older brothers and an older sister; the family continued to grow and Jack eventually had nine brothers and sisters. By 1908, when he was 18, he was living at Golspie, on the south-east coast of Sutherland, and by 1910 he was back living at Rogart, a few miles inland, where he wrote his book Scientific Athletics. He was brought up in an athletic family and in a culture that valued throwing and, although he was not a big man (nor a big boy or youth), he excelled in the throwing events, particularly the Shot and Hammer. Indeed, so slight was he that he created something of a sensation because he was very successful when very young and was much smaller than the people he competed against. In August 1908, the Aberdeen Journal described him at the Dornoch Highland Games as ‘a lad of 17 years of age and weighing 10 stone’ [140lbs/63.5kg] and ‘he was repeatedly cheered’ when he won the Hammer Throw (16lbs) [7.26kg] by 8 inches [20.3cm] and was second in Putting the Ball (22lbs) [9.98kg].

Jack Sutherland’s family was always an important part of his athletic life; in August 1908 (above), for example, it seems likely that his oldest brother, Andrew, was a prize-winner in the wrestling competition, and Donald, who was two years older, was a piper and an athlete, and won prizes in the Reels & Strathspeys competitions. In his book, Scientific Athletics, Jack Sutherland includes a photograph of “D. Sutherland, Rogart” (p. 63) and in Chapter XIX, Prominent Scottish Athletes and Their Performances, he describes D. Sutherland as a “successful all-round athlete” and gives details of his best throwing and jumping performances, but fails to mention that he was his younger brother. Donald was also known as The Rogart Hercules, but he was also an accomplished piper, and we hear of him later, composing pipe-music too. At about this time Donald left Scotland and went to Australia, from where he went to Peru before travelling to Oregon and finally settling in Montana. Neil, another brother, had also emigrated and lived in Montana.

In his early competitive years, writers repeatedly commented on Jack’s youth and his diminutive stature. In September 1908, The Aberdeen People’s Journal wrote, “A young athlete competed here, who promises exceptionally well. John William Sutherland, by name, he is 17 years of age, 5 feet 7 inches [1.70m] tall and weighs 10 stones 7 lbs. [147lbs/66.7kg].” They went on to say that he had thrown a 16lb Hammer ‘well over 95 feet [29m]’, putt a 22lb Shot 32 feet [9.75m], and ‘was good for 5 feet 3inches [1.60m]’ in the High Jump (ground to ground). All these distances can be authenticated in Sutherland’s own diary. He retained this boyish appearance throughout his athletic career and, in September 1911, the Aberdeen Journal again commented on his youth and size - “He was, to all appearances, the youngest athlete in the heavy events, and his victory was a popular one”; he was 21 years old and was still 5ft 7ins tall and still only 10½ stone [147lbs/66.7kg]. In that event he won ‘the Light Stone’ by over a foot with a throw of 38ft [11.58m], and won £2; this would be equivalent in purchasing power to £200 in 2021. By this date, however, his diary (as reported in Scientific Athletics) had come to an end, so we can only guess at how heavy the ‘light stone’ was. The John O’Groat Journal was to make similar comments about his age and size a year later.

John William Sutherland’s performances are not easy to trace; his performances were sometimes reported under the name, ‘John William Sutherland’, sometimes ‘J.W. Sutherland’, and sometimes ‘John Sutherland’, but in the same competitions there were other Sutherlands, and even a John, J, and W. Sutherland, and some were even from Golspie and Rogart. By June 1909, John William Sutherland had joined the Territorial Army and he competed in the Camp Sports at Burghead, winning the Hammer Throw for the 5th Seaforths (i.e. the 5th Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders).

Jack Sutherland’s diary comes to an abrupt end after reporting his results for August 1911; his entry for 18 August records that he had been at the Durnoch Highland Gathering and had been ‘indisposed’; nevertheless he set a ‘county record’ for the 16lb. [7.26kilos] Hammer, and putt the 15¾lb. [7.14kilos] ball 45ft. [13.72m], [listed as 15lb. [6.80 kilos] in the press] and high jumped 5ft 4 ins. [1.625m], but did not record in his diary that he was also 2nd= in the Pole Vault. He also failed to note that, although breaking a county record, he finished outside the first three in the event. Nevertheless, he was thought to be particularly impressive on that day with the John O’Groat Journal reporting that he was “well to the front” in the heavy events, “as he indeed nearly always is”, and that he went in for “a system of physical training and is particularly well developed for a young man.” It was, therefore, a good advertisement for the book he had started.

The entry for the following day (19 August 1911) records that he is still ‘incapacitated’ and ‘greatly indisposed’ but did compete at the Brora Games and competed in two Hammer, and two Putting the Ball events – but well below his previous standard. This entry is confusing and must have been added later, for he not only makes reference to the Brora Games which took place on 2nd September, but also to the Lairg Highland Gathering on 20th September, in which his performances were also below his normal standard.

1912 was both the pinnacle of Jack Sutherland’s athletic career and its effective end, and it all happened within a few days. On Friday 9 August Jack Sutherland opened his season at the Bower Athletic Sports, winning the 16lb. Hammer with 117ft. 1 inch [35.69m], and Putting the 16lb. Ball 48ft 10 ins. [14.84m]. He was also 2nd in the wrestling. His Putting the Ball performance was reported to be 1 foot 2 inches [35.5cms] better than the World’s Record, but was downhill; nevertheless, on the basis of those performances, he challenged A. A. Cameron, known in Scotland as the “World’s Champion”, to a series of events to decide the “heavy weight championship”. The challenge appeared in the newspapers one week later, on Friday 16 August. The Wick Riverside Committee was quick to seize on this and started to plan for the Sutherland/Cameron Championship Challenge to take place at the Wick Gala on Wednesday 28 August, just 12 days ahead.

On the same day that Sutherland’s challenge appeared in the newspapers (Friday 16 August), Jack Sutherland entered the Durnoch Highland Gathering, competing in the Open events, and also in the events open only to those born in the county – a very busy afternoon in which at the beginning of the meeting he “dislocated” the cartilage in his right knee in a Pole-Vaulting competition. As a result, in the County events, he was 1st= in the Pole Vault, but 2nd= in the High Jump, and 2nd in Putting the 16lb. Ball. In the Open events he was 3rd in the 16lb Hammer, 3rd in the 22lb.Hammer, and 3rd in the Long Jump. The “intense pain” clearly incapacitated him and he could hardly bend his knee; and before the week was out he had written to Cameron withdrawing his challenge. Jack Sutherland did not compete again in 1912, and in 1913 seems only to have competed once – at the Brora Highland Gathering - and was 2nd in the Open Hammer event, 10 feet [3m] below his performance of the previous year, and was also 2nd in Putting the 16lb Ball, over 9 feet [2.74m] less than the year before; but that was the end of his athletic career in Scotland. Almost immediately he emigrated to America.

Despite recording a 16lb. putt further than the World’s Record, J.W. Sutherland is remembered in athletics history only for his book, “Scientific Athletics” which he wrote when he was under 21, perhaps the youngest ever author of a technical book on athletics. He writes with such authority and certainty that any reader not knowing his age might imagine the author to be a white-haired veteran. He writes with a florid style, seldom choosing a short word when he can find a longer one; he also writes a series of articles for the John O’Groat Journal, writes replies to his newspaper correspondents, and also probably reported on his own performances in his very distinctive writing style in the John O’Groat Journal, but under the nom de plume “X.Y.Z.

Perhaps we should not expect him to reveal everything about his life in Scientific Athletics; he does not, for example, mention that he and his brother Donald gave weight-lifting demonstrations in the local drill hall and offered a prize to anyone in the audience who could emulate them – a prize that was never won. He also doesn’t mention the importance in his life of piping. From childhood he was exposed to the bagpipes and he and his brothers all played; indeed, even as children they learned how to make them, and learned how to burn holes with red-hot wires in the wooden pipes (chanters) on which they would later make music. The chanters were later attached to the bag made, perhaps, out of sheep-skin; and then the drones were added to form the bagpipes.

With at least two of his older brothers already settled in America, it is not surprising that Jack Sutherland wanted to try his luck there too and, in the autumn of 1913, he crossed the Atlantic and settled in Silver Springs, Clackamas, in north-west Oregon, close to the Canadian border. With his wife, Janess Elizabeth Sutton, he made his home there and became a schoolteacher; and he and Janess had three children. He was, however, a Scottish Highlander to the core and he began to compete in Highland Games there, ’though there are no records of his results, and he continued his piping and even wrote pipe-music. Jack Sutherland was a highly talented and versatile man and he not only played the pipes, he was also an unusually talented composer and teacher of piping. One observer wrote of him as “an accomplished and talented piper with a very keen understanding of the subtleties of the music” but was so eager not to be seen to outshine his brother Donald, he kept his real musical talents partly hidden.

Jack Sutherland was a highly talented and accomplished man but he was also full of contradictions; his writing revealed him to be self-assured and confident, and he always performed well when under the pressure of competition and in front of a crowd, but those who knew him described him as shy and modest; later, his son even called him a private person. Very unusually, no photographs exist of Jack Sutherland, with the exception of the portrait shot of his shoulders and the back of his head in Scientific Athletics (facing title page); one contemporary Scot explained that Jack Sutherland may have “felt circumspect about photographs, like many Gaels of his day.”

In Oregon, Jack Sutherland continued to follow athletics all his life. In a letter to his brother Andrew after the 1968 Olympic Games, he commented on the Russians’ perceived lack of success and regretted that Neil [Neal] Steinhauer, an Oregon thrower, had been unable to compete because of a “sprained back”, recalling that he (Steinhauer) had thrown 69 feet [21.03m]; and he mused on the fact that back in his youth, in the days of Scientific Athletics, he had thought 50 feet [15.24m] to be just about the limit of possibility! His interest in an Oregon thrower shows, however, that although a complete Scottish Highlander, after more than fifty years in the U.S.A., John William Sutherland had also become a thorough American. He died in 1970 at the age of 80.

The place of Sutherland’s “Scientific Athletics” in the history of Athletics literature:

The brash confidence of youth shines from every page of Scientific Athletics. Although published in 1912 when the writer was 22, internal evidence suggests that it was completed a year earlier and added to just before it went to press. The book is self-published with the author’s signature embossed in gold on the cover - quite a statement for a young man of 21! His purpose was to increase the popularity of athletics and calisthenics, and to give instructions on all the throwing, jumping and running events. But he knew that many would wonder how he could have the temerity to do so at such a young age - “some of my readers may be surprised that I should assume such an authoritative attitude in regard to so important a subject”, he wrote, which was probably something of an understatement. He saved himself, however, by addressing himself to the novice who might learn from his own experience as a very successful young athlete.

He did believe, however, that he had special insights into the athletic events and into athletic ability and training generally, and that those insights gave him the authority to tell others how to do it - his insights were centred around the word scientific, and included calisthenics and the latest ideas on Physical Culture. He gives no sources, except to quote ‘Dr Guthrie’ [Dr Thomas Guthrie, a Scottish preacher, temperance campaigner and philanthropist], but Sutherland was clearly an admirer of Arthur Saxon, a German strongman, and he also included photographs of Maxick [Max Sick, another German strong man] and Monte-Saldo [aka Alfred Montague Woollaston, from Highgate in London] in his book. The last two, however, seem to have little or nothing to do with the text and may have been part of an advertising deal whereby ‘Maxick & Saldo’ put money into Sutherland’s book in exchange for advertising space, including advertisement for a postal tuition course and, perhaps, two photographic plates placed within the text. There are also four pages of advertisements at the end of the book, which presumably helped offset some of the book’s costs. There were also advertisements from a strength and fitness magazine, and from Maxick and Monte-Saldo.

The value of Scientific Athletics is not in the chapters on The Efficacy of Athleticism and How it is Ensured, or the Acquisition and Conservancy of Vitality, or in any of the other fourteen chapters that make up the book, but in the twelve pages at the end of the book in which he gives extracts from his Athletic Diary from 1902 to August 1911 (i.e. from the age of 12 to 21). This is a unique account of an athlete’s development, and in great detail; for example, he has entries for eight different dates in May 1908 alone, and 11 dates in June 1910! They are only ‘extracts’ however, but we can fill in some of the gaps from other sources. For example, he competed in the Thornton Highland Gathering in July 1909 but does not list it in his diary; and in 1911 he competed at the Durnoch Games and lists the events he competed in, but he does not list all of them - other sources show he was also 2nd= in the vault. One of the difficulties in interpreting his diary is that he seldom gives venues; we usually have to find out where the performances took place from other sources. There are also inexplicable inconsistencies in the diary; for example, he reports ‘a new county record’, and a personal best, of ‘110ft 2in [33.58m] - two feet over own previous record’ in August 1911, but he earlier lists many that are even better! Nor might his diary always be accurate; for example, he reports in his diary that he threw the 16lb hammer 99ft. 7in. [30.35m] and the 22lb. ball, 32ft. [9.75m] at the Durnoch Games in July 1909, but the Aberdeen Journal report of that meeting describes him as 2nd in the hammer with 100ft. 7in. [30.66m], and 3rd in the 22lb. ball with 30ft. 5in. [9.27m]. So, although his diary is not complete, is sometimes apparently inconsistent, and not always accurate, no other book of this period gives so much detailed information about athletic progression, or so much insight into an athletic culture.

He also has useful chapters on -

*World’s Records and other remarkable achievements in athletics (though sadly without dates).

*Prominent Scottish Athletes and their Performances (which is very useful and contains some dates).

*Results from the 1908 Olympic Games (with some results reported in metres and some in feet and inches), and

*Martin Sheridan’s records as ‘Champion All-Round Athlete of America’.

There are 29 photographic illustrations, 11 of the author demonstrating various training exercises, and a portrait of Donald Sutherland, almost certainly one of his older brothers.

Peter Radford

2015 (revised November 2019; second revision August 2021)

The text:

Scientific Athletics provides us with a brief, tantalising, account of the athletics career of John William Sutherland, a young Highland Games athlete, in the period immediately prior to the Great War. This was the point at which the Games and their Border counterpart were at their peak. The Great War was to end the development of that rich athletics culture, blighting every hamlet the length and breadth of the nation. For, though the standards of the Highland Games were to rise subsequent to World War Two with an influx of amateur athletes, their numbers dropped substantially after the Great War and the Border Games withered. Neither would ever again be that expression of national vigour that they had been in the first decade of the century.

Sutherland’s book must be read with “Men of Muscle” and “Athletes and Athletic Sports of Scotland” if the historian is to secure a picture of what was a vibrant and extensive sports culture. It was one which extended far beyond Scotland’s borders, and which was to be a major influence on the early development of athletics in the United States.

Sutherland records in minute detail his progress from the age of eleven, hurling light shots and hammers into the turf of his father’s fields, to 1912 when at the age of twenty he puts the 16 pound shot to forty eight feet ten inches at Bower Games.

Extracts from the author’s Athletic Diary.

1902, aged 11 years, weight six and a half stone

September. 7lb. hammer 42 feet.

October. 10lb shot 21feet. 7lb. hammer 44 feet.

1906 (age 15)

16lb. shot 30ft. 18lb. shot 27ft. 6in.

18lb. hammer amateur style. 76ft.

Pole vault 8ft.2in.

Hop step and jump 34 ft. 3in.

High jump 4ft. 8in.

Finally, to 1912, after page after page of his training-notes, and to the columns of the John O’Groats Journal, and to its report on the Bower Games.

Sutherland is only 21 years of age, weighs not more than 10st. 10lb., and stands but 5ft. 7in. high; yet he putted 16lb. ball 48ft. 10in.,

and threw a hammer of like weight 117ft. 1in. The former distance is 1ft. 2ins. over the present world’s record, established some

years ago by an athlete of 6ft. 1in., and weighing about SEVEN STONE more than Sutherland…

He attributes his prowess to (1) methodical training; (2) indefatigable assiduity and perseverance; (3) abstemious habits; (4) teetotalism;

(5) great concentration of will …

The bulk of Scientific Athletics is devoted to an unexceptional description of each event, but Sutherland also attempts to give an account of the Games’ performances of his period. It is understandably incomplete, but one performance stands out, and it is that of his friend George Murray, who in 1907 achieved a long jump of 23 ft. 9 in., a mark which would have won him a silver medal at the 1908 Olympic Games.

It is ironic that Sutherland’s performance was achieved in 1912, a year in which Swedish amateur athletes had spent over three months in full-time training, all paid for by their government. Yet Sutherland and his “professional” colleagues, having earned a few pounds at their local Games, were banned from Olympic competition.

Even now it is difficult to read Sutherland’s account of his ten years of solitary training without a tear. For in bleak, remote Rogart, a young man trains from childhood, through adolescence into manhood, in daily challenge with himself. A true athlete.

Tom McNab/2015

Bibliographic details:

Title:

Scientific Athletics

Publisher:

Self Published

Place of Publication:

Rogart, Sutherland, N.B. (i.e. North Britain - Scotland).

Date of Publication:

1912

BL Catalogue:

General Reference Collection D-7904.aaa.19.

"An Athletics Compendium" Reference:

A346, p. 31.